He who has learned to disagree without being disagreeable has discovered the most valuable secret of negotiation.

- Chris Voss, Never Split the Difference

This is the fourth post in a series. You can find the last three here: 1, 2, 3. There we set the basics of opting out of negative games, and now we can start diving into examples.

A classic example of a negative game is the adversarial distribution of limited resources. In such situations, you might be fighting with others over the same set of stuff, whether it is the proverbial pie, or that promotion which only one person will get, the custody of a child, or even who gets to speak in a conversation.

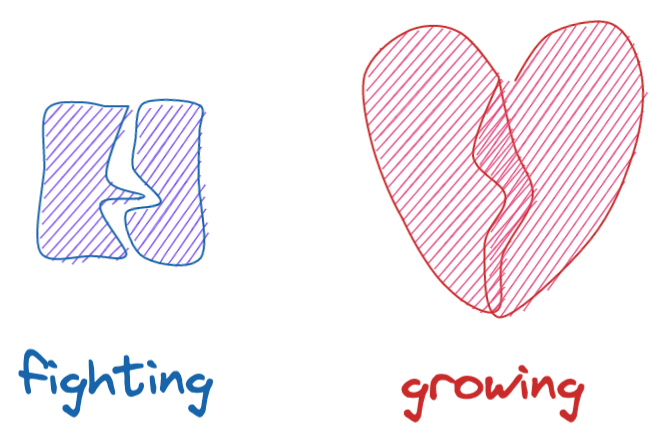

One way to exit such game, is to change the vibe from competition to cooperation, to increase these limited resources.

For example, if we consider a divorcing couple which fights over the custody of their child, we can see that what they’re really fighting for is the satisfaction of their own egos, and not the best outcome for the child. By treating that child as a limited resource to fight over, instead of a person, which both want to support, and instead of discussing how to make the transition less traumatizing for the kid, they end up creating more trauma for the child, as the child will lose one parent. However, if the parents care more about their children’s future than about their own egos, they might find an arrangement where the kids experience more love from both parents, and grow up to be more fulfilled. The parents can opt out of bickering by realizing they still have a shared vested interest in their kid’s wellbeing, and change the “vibe” of the conversation.

More generally, in any conversation you may try to convince the others of something, and think that the way to do it is to spend more time talking. You might see the time during the conversation as a limited resource and try to capture most of that time by speaking more, and speaking louder than others. And doing so, you might make it harder for others to express themselves, creating a competitive argument. A shouting match of loudly saying “Me, me, me!” As a result, you’re not going to be effective at convincing, and will not even contribute to information transfer. When you’re trying to talk, you’re not trying to listen. If you instead try to play the game of increasing information transfer, regardless of the direction, you stand a better chance of persuading others, and you are also allowing yourself to have your worldview improved.

In the last example today, we look at the Red Queen’s race. A company entering a crowded market may be fighting for market share with other companies, selling to the same customers. That company may even be successful if the incumbent are not providing a good service. And if these companies are fighting over the same market share, they end up both cutting costs and price, and undermining each other’s profit. A way out for a company is to figure out how to grow the market and capture that new growth, by serving an underserved population or use case which wasn’t in the market previously. Focusing on beating the competition is zero-sum thinking, but focusing on the customer is a win-win thinking.

Next week, we will discuss artificial scarcity.

Thanks to Sylvain Kieffer for spotting grammar typos in this post.